Racial Trauma & Responding to Racism

An article about historical trauma and ways to respond to racist incidents.

by Chandra Ghosh, PhD

When faced with painful moments involving race and culture, we all respond differently based in part on our past experiences. Some of us may have personally experienced racism frequently, others may be facing these moments for the first time, or witnessing it directed toward someone else. Skillfully addressing moments like these with children requires practice. Just like physical exercise, it may be hard to start, and there may be pain or discomfort at first, but with work, muscles will grow stronger. Check out this video as a place to start.

As we work together in our communities to build strength in this area, it’s important to recognize that these moments affect each of us differently, depending on our family histories. A moment in which a child rejects another because of race or cultural background can bring up personal memories related to oppression, violence, or exclusion. A moment like this can also serve as a reminder of historical and ongoing trauma—times in which a racial or cultural group was mistreated so badly that those people were in danger within our society. When that’s the case, of course, it will hit both children and adults harder, and we’ll have a stronger response.

Racism can show up in many different ways, and children may say or do things that reflect racist messages they have heard from adults or other sources. For instance, they may repeat negative comments they have heard about others who are different from them.

And here are options for how any child or adult (whether or not they are the target of racism) might respond in these moments. Consider thinking about the difficult moments you yourself have experienced or seen, and then breathe, feel, share—partner with others—to grow our collective responses to these moments so you’re in a better position to support children. Depending on children’s age, you might suggest that, when encountering one of the above scenarios, they:

- Answer questions with simple, proud explanations: “My hair looks like this because I’m Black. Different groups of people look different ways and that’s what makes the world interesting. I like my hair.” Or “My name is from my first language, [name of language]. It means [meaning] and it’s special to me and my family.”

- Share their reaction: Children can keep their responses short and simple (“Wow.” “Seriously?” “Ouch.” “Not kind.”). If the person apologizes, they can move on. If not, then that’s someone who is not going to be a good friend. It’s time to move away and stop talking to them, and ask a grown-up to help.

- Share their view of what they said: “What you said is mean.” “That’s unkind.” “That’s not fair.”

- Show curiosity: “I wonder why you said/think that.”

- Repeat and emphasize what they said: Children might speak slowly, showing their surprise and shock to highlight that what the other person said is not okay (“You said, you can’t play with me because…”)

- Disagree: “That’s your opinion/choice, but not everyone’s, and it’s not right.”

- Connect the other person’s behavior to history and share a wish for change: “A long time ago, people used to think that [some groups of] people were better than others, and they treated [other groups] really badly. They were wrong, and it’s time for things to change.”

When we understand these racist moments as both painful in their own right and possible reminders of historical trauma, we can appreciate that when we encounter such moments, we may have the typical responses of those who have experienced trauma:

- Fight: Feeling a strong verbal or physical response to defend ourselves from attack

- Flight: Wanting to run away, escape, or avoid the situation or person

- Freeze: Not being able to respond, not feeling present in these moments

- Fawn: Trying to please the person who caused the harm

In these moments, the “Breathe, Feel, Share” strategy may serve as a strategy not only for children but also for the adults who support them. “Breathe, Feel, Share” can help us regulate our emotions, feel more whole, and be better able to respond.

In a racist moment, adults and children alike might start by feeling flooded with feelings, including understandable anger and sadness. We can take this opportunity to slow down and be kind to our bodies and ourselves by breathing deeply. As we become more in touch with our feelings and bodies, we might decide to reach out for support, such as talking to a trusted friend or family member who might validate our feelings.

As we consider both what happened and its impact on us, we may recognize that there are different ways we might respond. Having choices and greater confidence in our ability to respond can make the moment feel less overwhelming and stressful.

Children need our support in finding developmentally appropriate ways of responding. When we help them consider their options, they can better move from feeling stranded with the experience to feeling connected. They can move from feeling silenced, frozen, and overwhelmed, to feeling like they have the ability to say or do something if they want to. Having these options can help make a painful moment less stressful and possibly less traumatic.

Chandra Ghosh Ippen, PhD is a child psychologist and children’s book author. She is Associate Director of the Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco, Director of Dissemination and Implementation for Child-Parent Psychotherapy, and a member of the board of directors of Zero to Three. She has spent the last 28 years conducting research, clinical work, and training in the area of childhood trauma and has co-authored over 20 publications on trauma and diversity-informed practice.

The Wiggle-Jiggle Game

A video about a getting-to-know-you game that helps kids appreciate similarities and differences.

Welcome to Our Garden

An interactive game in which children add rocks to the Sesame Street community garden.

Community Song

A video about community.

Musical Show & Share

A video about coming together to create something beautiful.

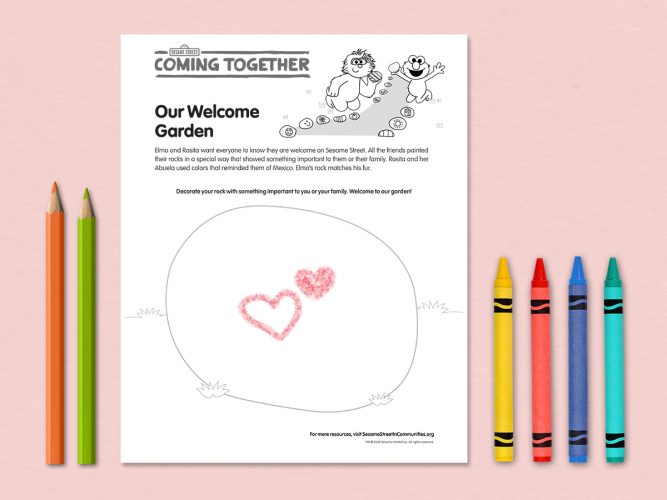

Our Welcome Garden

A printable page about a community rock garden.

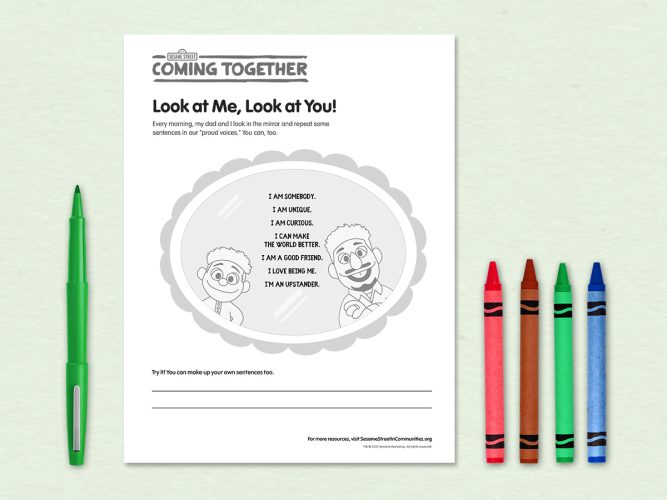

Look at Me, Look at You!

A printable page with parent-child affirmations.

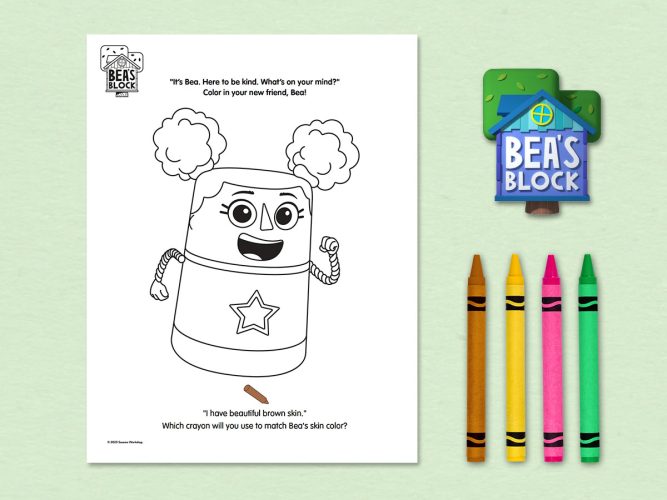

Bea’s Block Kindness Adventure Color & Activity Guide

Activities and coloring pages for children that celebrate kindness.